By Meghna Bal and Chhavi Pathak

The suicide of three sisters in Ghaziabad triggered widespread concern around “Korean love” games. Public discourse reduced the issue to dangerous games or foreign influence. Our investigation identifies a deeper concern: Research shows that “Korean love” or Otome games primarily attract young women and adolescent girls, especially those facing social anxiety or limited offline interaction. While adults may treat these games as fantasy, adolescents remain more vulnerable to immersive emotional attachment. Otome games do not rely on explicit self-harm tasks like the Blue Whale challenge. They rely on feelings of loneliness to embed users in simulated romantic relationships. The risk arises not from explicit self-harm tasks but from engineered parasocial attachment. India’s regulatory discussion remains focused on bans and screen-time limits. Effective oversight must move beyond reactive censorship and confront the factors that shape online adolescent engagement.

On February 4, 2026, three sisters aged 12, 14, and 16 jumped from the ninth floor of their apartment in Ghaziabad. Early media coverage attributed the deaths to an online “Korean love game” that the girls had allegedly played obsessively. Subsequent reports clarified that investigators had not conclusively linked a specific game to the incident. Reports nevertheless speculated a correlation between the incident and the sisters’ deep immersion in Korean pop culture and an abrupt loss of digital access. The girls reportedly maintained alternate “Korean” identities online and shortly before the incident, their father had deleted their YouTube channel and confiscated their mobile phones.

The Ghaziabad incident raises several questions about how teens and pre-teens inhabit digital spaces. What are these so-called “Korean love games”? How do these platforms function? Why do they appeal to tweens and teens? How are they able to command sustained, and at times intense, engagement from adolescents?

To understand what a “Korean love game” is, we mapped conversations across digital spaces where K-pop “stans” (superfans) routinely engage, including X, Instagram, TikTok, Snapchat, and Reddit. This mapping exercise led us to a game titled Pika, which in turn surfaced recurring hashtags such as #MysticMessenger and #ObeyMe! A review of these games revealed that a genre popularly known as “Otome” (japanese for maiden). Otome games are narrative-driven dating simulations primarily marketed to young women. They typically centre around a female protagonist who navigates romantic storylines through interactive choices that shape character relationships and plot outcomes. There are also versions for males, where the player is a male protagonist pursuing bot love interests, called Galge.

Figure 1: Otome Game

Otome games originated in Japan and entered South Korea in 1997 after trade opened between the two countries. Korean developers soon began producing their own titles, beginning with Megapoly’s Love series. The genre, however, evolved significantly with the launch of Mystic Messenger in 2016, which introduced real-time messaging to simulate direct interaction with fictional characters. As Korean popular culture expanded globally through the Hallyu wave, Otome games followed, securing a growing international audience.

The Otome gaming market expanded rapidly across the Asia-Pacific region. Industry estimates value the Asia-Pacific Otome market at USD 1,210.77 million in 2024, with projected growth at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 12.6 percent between 2024 and 2031. In India, the Otome gaming segment was valued at USD 38.629 million in 2021 and is projected to reach USD 56.033 million in 2025, growing at a CAGR of 9.551 percent.

We downloaded several of the most visible English-localised versions of Otome games available in India and created user accounts for a minor user. We used the applications without changing the default settings to simulate an adolescent user journey and progressed through early narrative chapters without purchasing premium currency. We documented onboarding flows, reward cycles, monetisation triggers, and message frequency. This engagement allowed us to observe the mechanics directly rather than rely solely on media characterisations.

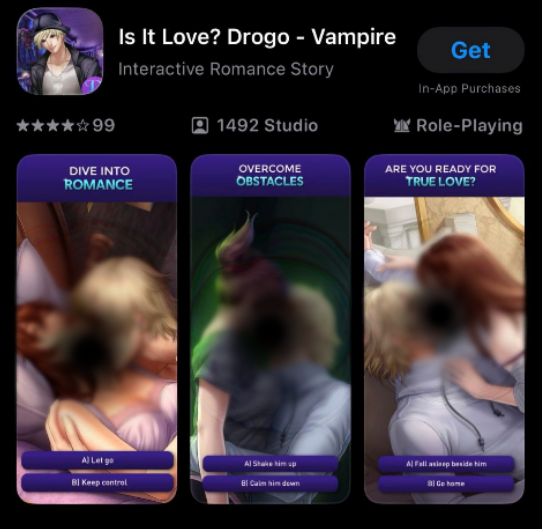

Our hands-on review revealed a consistent design pattern. The game positioned the human player as the main character. It gave our player a unique (usually Korean) identity. Characters addressed the user by the given name. They sent timed messages that required prompt responses to maintain “affection levels.” Certain narrative branches remained locked unless the user logged in at specific hours or used premium tokens (which had to be purchased). Missed interactions triggered subtle emotional cues, such as disappointment or distance from other characters. The platform rewarded sustained engagement with exclusive scenes and heightened intimacy arcs. For instance, in Picka, every time one chat wound up with one character, another would begin.

Figure 2: Screenshots from conversations in the Picka game

The platform design manufactured a perfect environment for creating a parasocial relationship. A parasocial relationship refers to a one-sided emotional bond between an audience member and a manufactured persona usually belonging to an actor, character or influencer. A recent study exploring the mechanisms of romantic relationship formation within Otome games revealed that parasocial romantic relationships formed in Otome games are not entirely detached from reality. They are embedded in daily life through game interaction mechanisms and the players’ internalized imagination. These relationships influence the reconstruction of real-life intimate relationships. Female players show a high degree of acceptance and immersion in these romantic relationships, focusing on the emotional support provided by male characters.

Adults often engage with Otome games as fantasy and use these platforms to regulate emotions, explore identity, or experiment with ideas of intimacy. However, minors do not operate from the same developmental baseline. Adolescents are still forming relational schemas and impulse control. They are more sensitive to social reward and romantic validation, which increases susceptibility to intense emotional attachment and blurred boundaries with fictional characters.

Research suggests that the core user base of Otome games consists largely of young women and adolescent girls, particularly those experiencing social anxiety, limited offline interaction, or dissatisfaction with real-world romantic prospects. Within this group, heavier engagement with romantic simulation media has been associated with heightened body image anxiety and diminished interest in real-life romantic relationships.

Since news of the Ghaziabad incident broke, many reports have compared it to the Blue Whale challenge. However, such a comparison is based on an inaccurate understanding of “Korean love games” which are structurally different from the Blue Whale challenge. The Blue Whale challenge relied on explicit, escalating self-harm tasks. The harm arising from the challenge was direct, visible and addressable. Otome games operate through a completely different modality. They cultivate attachment through interactive storytelling, timed responses, and personalised affirmation. The risk emerges from sustained emotional dependence engineered through platform design. These games specifically exploit a user’s feelings of loneliness and insignificance, to get them to continually engage, and very often, pay for emotional attachment or security they seek in their offline world.

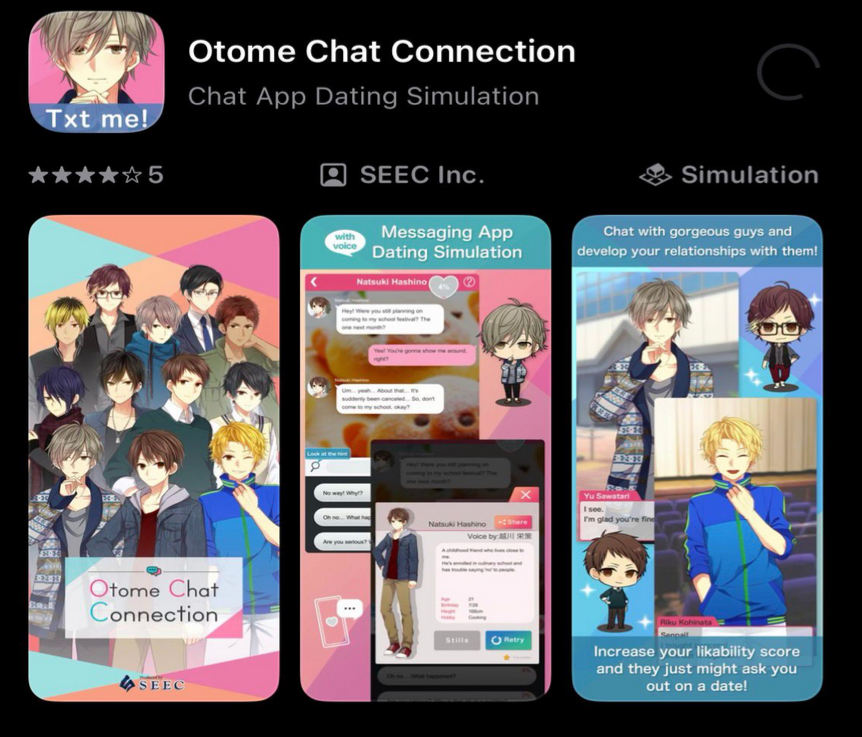

Another game we played, “Otome Chat Connection”, had the player interact with three distinct male personalities (impersonated by bots). The game would rate your response either “Excellent”, “Good”, or “Bad” based on the personality you were dealing with. You could not type out your own response, these were pre-written for you and you were required to choose among them. If you gave responses that the game rated positively, the male character’s love for you would grow (indicated by your “likability” score), whereas responses rated “Bad” corresponded with diminished affection. If you wanted a hint for the optimal response, you would have to pay. You also had to pay or watch ads to unlock more characters. This game encompassed the most overt weaponisation of loneliness and wanting on the part of the user among those we engaged with.

Figure 3: Screenshot of the Otome Chat Connection Game

India’s regulatory framework does not confront this form of harm. Existing rules target unlawful content, online betting and wagering, intermediary due diligence, and deceptive monetisation. They do not scrutinise immersive relational design, emotionally manipulative engagement systems, or age-inappropriate intimacy mechanics embedded in Otome games targeted at children.

The current discussion around regulating online gaming is restricted to suggestions of blanket bans or screen-time limits. Neither of these solutions will solve the problem arising from Otome games. Removing such applications from mainstream app stores will only push access to third-party platforms, VPNs, or anonymised browsers making harm less detectable. Moreover, any regulatory proposals seeking to encourage sideloading will only enhance the accessibility of these games.

There is a need to move beyond episodic bans and reactive censorship. Regulating Otome games and the harms that come with them requires deeper thinking about platform design obligations and digital literacy initiatives addressing parasocial dynamics and immersive storytelling. Most importantly, there is an urgent need to recognise and attempt to regulate the growing epidemic of adolescent loneliness by facilitating conditions that enable children to socialise outdoors, school-based mental health systems, and bottom up-driven engagement initiatives. Lastly, there is a need to ensure that any intervention, particularly when it comes to children, is supported by robust empirical evidence that incorporates and empathises with children’s perspectives.